CHECK IT OUT! APASWE: No. 36 (2019)

Decolonising social work education in Aotearoa New Zealand

David McNabb

School of Healthcare & Social Practice, Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland

Address for Correspondence:

dmcnabb@unitec.ac.nz

ABSTRACT

The social work education sector has a vital role to play in advancing the rights and interests of Indigenous peoples. Global and national standards reinforce this requirement and regulatory frameworks identify decolonising practices as important to the delivery of social work education. While standards influence and guide practices, the degree to which decolonising practices are operationalised at the local level depends upon programme delivery within higher education. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with social work education leaders in Aotearoa New Zealand to explore how decolonising practices were demonstrated within their programmes. The research found that all programmes were committed to a decolonising approach but struggled in different ways to operationalise this commitment and to maintain momentum. Having Mãori staff was seen as essential but there were too few, and meeting regulatory qualification requirements was problematic.

Integrating Mãori knowledge and practices within the curriculum was also vital for student learning and building their cultural responsiveness. Non-Mãori staff had a particular responsibility to acknowledge the harmful effects of colonisation and to practise respectful partnership with Mãori. The role of leaders and staff in the operationalising of decolonising practices within social work education is explored for future implications of policy and practice development.

Keywords: Decolonisation; Indigenous; social work education; leadership; standards; regulation; Mãori; Aotearoa New Zealand; Australia

INTRODUCTION

Before discussing decolonising social work education in Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa New Zealand, including both indigenous and colonial names), it is important that I situate myself as a Pãkehã, or White social work educator with Scottish, Irish and English roots that go back to my forebears who arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand in 1843. I have learned from and consulted with a range of people and, in particular, Mãori colleagues. I am grateful to them for their insights and for those who were willing to participate in the research. I particularly wish to acknowledge the contribution of Professor Marie Connolly in the development of this article. As sole author, I nevertheless take full responsibility for undertaking and reporting the research, and for the conclusions that are drawn.

Indigenous rights and decolonisation

Indigenous peoples have been fighting for their traditional rights ever since colonisers took their lands, wealth, labour, culture and language. The rights and expectations of Indigenous peoples have found their contemporary expression in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (United Nations, 2008). Globally, colonised peoples have mobilised in protest and have been at the forefront of the fight for change.

Whereas people of colour have often been the colonised group, European or White people are usually part of the dominant population. In general, dominant group forces have been slower to support decolonising developments but can become important allies in creating societal change (Huygens, 2016).

From the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, Tuhiwai Smith (2012) notes that decolonisation was once only defined as the formal handing back of the governance of a country by the colonial authority but “is now recognised as a long term process involving bureaucratic, cultural, linguistic, and psychological divesting of colonial power” (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012, p. 175). Some have used the extended term decoloniality to emphasise the depth to which colonisation negatively affects the colonised group and the challenge facing the colonising group in addressing the knowledge of this harm. This highlights the work needing to be done with the colonising group for a more equitable society to emerge – including within the context of social work education (Hendrick & Young, 2018).

A critical analysis of colonisation and of race has challenged privileged status to confront the advantages that have been accrued by the dominant group and to take a stand against injustice and racism. Indigenous people challenge non-Indigenous people to take respons- ibility for addressing White privilege as a prerequisite to becoming allies in the work of decolonisation (Bennett, 2015). The concept of ally has been developed by Bishop (2003) and has been used by many groups working for change.

The term White privilege initially arose out of the critical White studies movement which spread to other parts of the world in response to challenges from black voices in the USA. Young and Zubrzycki (2011, p. 162) note the seminal work of Peggy McIntosh whose essay “White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack” in 1989 was important in identifying the often unseen and unacknowledged benefits of being White. The field of critical White studies, which incorporates the notion of White privilege, interrogates the ways in which this privilege “is raced and invisible; [providing] a method of unsettling this privilege;

and it offers guidance for more inclusive and respectful human relationships” (Young & Zubrzycki, 2011, p. 165). The wider theme of privilege has been explored by Pease (2016) including a focus on understanding the benefits of privilege by those in the dominant group and their complicity in others’ oppression.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Mãori have led the resistance to colonisation and its effects. In 1835, He Whakaputanga - the Declaration of Independence, was signed by Northern chiefs in Aotearoa New Zealand and recognised by Britain (Orange, 2015). Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Indigenous Mãori language version of The Treaty of Waitangi, hereafter Te Tiriti) was signed by a number of Mãori tribal leaders and the British Crown in 1840.

Whereas Te Tiriti held the hope of a mutually beneficial arrangement for Mãori who signed along with the British Crown, including the notion of “bi-polity” where two sovereign nations could equitably govern (Ruwhiu, Te Hira, Eruera, & Elkington, 2016) the dominance of Britain was asserted and Mãori experienced colonisation of their land and indeed, their whole world. Mãori resisted colonisation, land battles were fought while, at the same time, Mãori adapted to Western ideas and technology.

In contemporary times, Mãori have protested for their rights and now through the Treaty of Waitangi Tribunal a number of iwi (tribes) have settled historic disputes with the Government. This has typically included an apology from the Government for the land taken and harm caused, and financial and other components of redress. At one level, decolonisation has been formally under way with a growing number of tribes engaging in the settlement process, since the Treaty of Waitangi Tribunal was established by an Act of

Parliament in 1975, although it is acknowledged there is a long way to go (Huygens, 2016). On the other hand, it can be argued that any decolonisation process is limited due to the significant ongoing colonial legacy of major structural deprivation faced by Mãori (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012). Alongside the negative structural impact of colonisation, Te Tiriti continues to offer the potential of partnership between Mãori and non-Mãori.

Within the Aotearoa NZ education context, Mãtauranga Mãori (Mãori knowledge) has been recognised as one of the guarantees of Te Tiriti and embedded within the education legislation of 1990. One example of the development of Mãtauranga Mãori within a public education institution involved a tool being created, Poutama, to assist all its programmes to honour Te Tiriti (Unitec Institute of Technology, 2011).

In the context of Mãori self-determination we note the advent of Wãnanga (Mãori-based institutions) as a key site for decolonisation and indigenising practices also expressed in the context of social work education (Akhter, 2015). Other global manifestations of indigenous tertiary institutions include the indigenous university based in Canada, established in 2004 (Young et al., 2013).

Decolonising global social work education

Decolonising social work education is a global aim that unites countries with colonial histories. Some of the literature is contained in edited texts on the theme of indigenous or decolonising social work education and research (Gray, Coates, Yellow Bird, &

Hetherington, 2016; Fejo-King & Mataira, 2015; Zubrzycki et al., 2014) and many texts focusing on social work education with broader indigenous themes – in Aotearoa NZ (Crawford, 2018); in Asia Pacific (Noble, Henrickson, & Han, 2013; (Nikku & Hatta, 2014), and globally (Noble, Strauss, & Littlechild, 2014).

Countries in which decolonising and indigenising social work education is being advanced include: Aotearoa NZ (Anglem, 2009; Eketone & Walker, 2013; ); Australia (Fejo-King, 2013; Muller, 2014); Canada (Johnson, 2010; Waterfall, 2008); the Pacific including Tonga (Mafile’o, 2004); Samoa (Faleolo, 2013); and the Pacific more generally (Mafile’o & Vakalahi, 2018); the USA (Yellow Bird, 2016) including Hawai’i (Morelli, Mataira,

& Kaulukukui, 2013); China (Yuen-Tsang & Ku, 2008); South Africa (Harms Smith & Nathane, 2018), and Africa more broadly (Kreitzer, 2008); the Sami in the Nordic region (Merja, Sanna, Merja, & Sanna, 2016); the Americas more broadly (Tamburro, 2013); also Central and South America, and Europe (Young et al., 2013). Broader spiritual and religious themes can be aligned with the indigenisation project such as a text on Buddhist Social Work that roots practice in Asia (Gohori, 2017) and exploring the links between Islamic spirituality and indigenous social work education (Akhter, 2013).

The Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) Code of Ethics, Reconciliation Action Plan, and Education Standards (AASW, 2012) privilege Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing within the curriculum and the broader practice of recognised social work programmes. A key document for Australian social work education, the Getting It Right Framework (Zubrzycki et al., 2014) provides a teaching and learning framework to advance decolonising efforts in social work education in Australia. The four key features of the framework include Indigenous “epistemological equality, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-centered social work, cultural responsiveness, and Indigenous pedagogy” (Young et al., 2013, p. 1).

However, because social work is a profession that originated in the West and continues to sit within a stream of colonisation, it has a problematic relationship with Indigenous peoples. This is why the Getting It Right Framework (Zubrzycki et al., 2014) argues that the social work profession must critically reflect on how it contributes to ongoing colonising practices and that White privilege must be addressed within social work education. Addressing non- indigenous privilege in the educational context can be informed by the broader notion of a pedagogy of privilege, where recognising one’s own privilege and the benefits it brings is vital along with continually challenging the systems that supports it.

Literature exists more broadly about race and racism, and how this can be addressed within the educational sector. Anti-racism practices include using agreements for “courageous con- versations about race” at the classroom level, with leadership required at the institutional and policy levels (Singleton, 2015, p. 15). Racism covers a broad area of oppression whereby one cultural group discriminates against another based on biology and cultural difference, usually White against people of colour, with both structural and personal dimensions of oppression. Colonisation involves “the process by which European imperial powers gained military control of and subjugated the peoples of ‘colonies’ in Africa and Asia” (Gray et al., 2016, p. 333) and, of course, in the Pacific. Both racism and colonisation are identified components that should be addressed in decolonising social work education (Zubrzycki et al., 2014).

Indigenous knowledge must be recognised as equivalent to Western knowledge creating “epistemological equality” (Zubrzycki et al., 2014, p. 17). In the Aotearoa NZ context this has been incorporated into the promotion of Mãtauranga Mãori (Mãori knowledge) a feature which aligns well with the commitment of the Aotearoa NZ social work profession to honour Te Tiriti (Aotearoa New Zealand Association of Social Workers, 2013).

From a global and local perspective, regulatory frameworks provide opportunities to shape the ways in which social work education is developed to support democratising and decolonising practices (McNabb & Connolly, 2019). Standards provide a foundational platform on which best practice can be developed, and in this regard it has been argued that the role of leaders is to move social work education beyond baseline standards toward aspirational goals such as decolonisation (McNabb, 2017). Recent research identified democratising and decolonising practices as key themes that have been reinforced in the Global Standards, and the local standards of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand (McNabb & Connolly, 2019). Further research has examined the ways in which democratising practices are given effect within programmes of social work education across Aotearoa NZ (McNabb, 2019). This adds to a growing body of literature that explores the influence of regulatory frameworks on social work education (McNabb & Connolly, 2019).

This article explores the ways in which leaders of social work education in Aotearoa NZ support decolonising practices within their programmes alongside their thoughts on the challenges and opportunities of demonstrating an enduring commitment to Te Tiriti and to advancing the partnership between Mãori and non-Mãori.

METHODOLOGY

The study undertook qualitative interviews with social work education programme leaders to investigate questions relating to decolonising of practices in Aotearoa NZ. One of the more common forms of qualitative research is the semi–structured, face-to-face interview of individuals (Brinkmann, 2013). This approach was particularly useful in this study as it allowed a more nuanced and richer conversation with leaders about the challenges and issues arising from advancing decolonising practices in social work programmes.

Leaders of all 19 social work programme providers were invited to participate in the study ranging across university, polytechnic, Wãnanga and private institutional contexts. Unlike some countries where social work education is confined to universities, in Aotearoa NZ there is a diversity of tertiary education institutional contexts. By engaging with a range of providers, features of this diversity across the country were captured. These features include: metropolitan and regional geographies; polytechnic, private training establishments, universities, and Wãnanga institutions; Mãori, Pacific and mixed cultural settings; campus-based and distance mediums; small and large programmes; bachelor and master’s level programmes; and a special character faith-based institution.

Fourteen of the 19 programme leaders participated, providing a very strong representation of programmes across Aotearoa NZ. Two thirds of the respondents were women, and two thirds were Pãkehã (non-Mãori usually of British European descent). Leaders with Mãori, Pacific and Indian ethnicity were also represented. The role of leaders in social work pro- grammes in Aotearoa NZ is made more complex by the range and diversity of management and disciplinary leadership roles in the sector. These roles range from full management and leadership of the programme and its staff on the one hand, and roles focusing on disciplinary academic leadership without management responsibilities on the other. The respondents were roughly split in half between each of these categories.

Most interviews were conducted in person and where this was impracticable, online syn- chronous digital technology was used through the Blackboard Collaborate platform or through Skype. A semi-structured interview schedule was used that had been developed from the themes identified in the earlier document analysis, specifically relating to “service user and student participation, student representativeness, Indigenous rights and political action, gender and cultural equity, access and equity, and quality social work education and broader issues of equity” (McNabb & Connolly, 2019, p. 42). The NVivo data analysis software tool was used to assist in analysing the data thematically.

Ethics approval was gained from the Human Ethics Advisory Group of the University of Melbourne and the study was regarded as a minimal risk project; Ethics ID 1748887. All participants in the study gave informed consent.

In addition to the well-documented limitations of using a qualitative research methodology, there are limitations particular to this research which relate to the sample. Only interviews with social work programme leaders in Aotearoa NZ were undertaken, and the research does therefore not include the views of other social work academic leaders, academic staff, students or people who represent the wider social work sector including service users, iwi and Mãori organisations, community organisations and other stakeholders such as government. Research with these groups may well offer some different views about the nature of decolonising practices.

FINDINGS

The leaders were asked to share their perspectives with respect to decolonising practices, and the ways in which these practices were given effect in their social work programme. Whereas the leaders were not given a definition of decolonisation and its respective practices, within the context of Aotearoa NZ, any action to promote Mãori knowledge and culture, a deeper expression of commitment to Te Tiriti and partnership between Mãori and Tauiwi or biculturalism, would fit within a broad definition of decolonisation. These features of decolonisation are supported within the social work profession and within tertiary education policy.

Three key themes were identified: the commitment to decolonising practices; operationalising decolonising practices; and the enablers of decolonising practices. Each participant was assigned a non-identifying number which is noted beside each quote.

Commitment to decolonising practices

The importance of engaging with Kaupapa Mãori values was seen as a critical foundation supporting a programme’s commitment to biculturalism in practice:

Fuse those values that you know about, the Treaty values, and also other Mãtauranga Mãori knowledge values... and then we’re moving from that toward decolonisation [of the whole programme]. (11)

Mãori staff were seen as having a key role in this, a role that required institutional support:

One of the key parts of our… bicultural [journey] from a Kaupapa Mãori [perspective]… supporting the Mãori staff to start self-determining and owning key aspects of the programme and their place. (2)

In the context of decolonising practices, the leaders reinforced the deep commitment that social work education has to advancing Te Tiriti, and operationalizing the elements of Te Tiriti in practice. Establishing a firm foundation of responsiveness to Te Tiriti, was seen as critical to advancing practice. This involved establishing a strong Kaupapa Mãori foundation in each programme with a particular expectation of responsibility as leader:

As a manager or a leader, that’s where I see I have quite a high level of responsibility for the profession to ensure that we are being genuine in our commitment (to the Treaty), and I see my role as the enabler of that. (3)

One leader noted that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is complementary to Te Tiriti based practice and was making a link between the global and local decolonising efforts:

The UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People, I think offers us a very unique opportunity to unpack what our Treaty relationship might look like. (13)

One leader of a programme with a deep and enduring commitment to Te Tiriti noted a dilemma in having a strong Kaupapa Mãori based values where predominantly Mãori

students tended to work in iwi (tribal) services but might struggle to work in “mainstream” agencies due to the challenge of balancing Mãori and non-Mãori bodies of knowledge. In this instance, the importance of committing to a blended knowledge base was suggested:

I think our programme ... needs to be a lot stronger at that interface between Mãori and non- Mãori bodies of knowledge, because what we’ve found historically is that our tauira [students] have gone into statutory organisations and within a really short period of time they’ve felt quite isolated in terms of tracking their body of knowledge, which has primarily been from a Mãori perspective. (13)

A number of leaders spoke about being committed to a bicultural journey but of also being restrained by resourcing or policy settings within their institution:

The social work programme particularly is totally committed to the bicultural Code of Ethics and

teaching in a bicultural manner… But, our institute has not supported us well with that and it’s been a continuing challenge… (7)

On the other hand, when there was a clear, higher-level institutional commitment to advancing bicultural practices, there was a trickle-down effect that provided support for change throughout the organisation:

It came from the top, in terms of our commitment to biculturalism and in the context of colonisation. So, we’ve had conversations as a faculty about that… I think it’s flown through to our school and conversations at staff meetings, and it’s gone through to our programme level and it’s showing up in class. (6)

Social work education nevertheless exists within a context of colonised practices and some leaders noted tensions in operationalising decolonising practices in the context of competing expectations of evidenced-based practice.

This is something we now turn to in the next major theme.

Operationalising decolonising practices

Leaders articulated the challenges in meaningfully and purposefully shaping bicultural social work programmes and the ways in which it might be monitored and sustained, without being formulaic:

How many tertiary institutions will simply see this as a tick box exercise rather than necessarily a fundamental look at themselves? (13)

Some leaders also noted that the physical environment for learning Mãtauranga Mãori (Mãori knowledge) is important, including using marae (Mãori meeting houses) as a way of deepening a student’s knowledge through experience:

I think it’s also the mode of delivery. And this is what our tauira [students] say to us. The moment we walk through the door we felt at home... It’s a thriving [place]… And the students overwhelmingly have said to us that the penny dropped when they went onto a marae. (13)

What we ask students to do is to select an issue that is relevant to Mãori... and then they complete presentations on the marae about the issue and solutions... So, they have the opportunity to apply Mãori concepts, particularly tikanga [customary practices] and then to receive feedback. (8)

A number of leaders spoke about the challenge of maintaining momentum for a Tiriti-based programme. There were a number of facets to manage and any one or more could slow progress. Ongoing development of teaching practices that supported Mãtauranga Mãori in the programme was seen as critical. Where there was strong support from the institution, programmes moved from talking about decolonising practices, to operationalising them:

I think we’ve moved beyond caucusing to another era and so, looking at what is Mãori knowledge, how is Mãori knowledge taught, who does the teaching of Mãori knowledge, and

then how is bicultural engagement included and what are the steps that we can make; how is te reo [Mãori language] acknowledged? (2)

Leaders noted various ways in which the commitment toward biculturalism was operationalised. For example, aligning the curriculum in ways that reflect Te Tiriti, and integrating Te Tiriti within assessment processes in practical ways:

The Treaty and biculturalism form some of the backbones of our programme – the structural backbones. We declare ourselves to be a bicultural programme… In terms of delivering the pro- gramme, all our course outlines have to demonstrate how they meet the focus on biculturalism. (4)

Almost every assessment requires an examination of firstly the Treaty and then the community that you serve. (5)

Similarly, leaders explored the ways in which biculturalism can be strengthened through its integration into the whole curriculum, for example, by integrating Te Tiriti material in specific papers and also throughout the degree. The value of having had a quality assurance process during the construction of the curriculum that included a review by both a Mãori and a Pasifika (Pacific Island) appraiser was also noted:

And all of it is reviewed by a bicultural appraiser and Pasifika appraiser; so, you have Mãori and Pasifika perspectives reviewing our content, the whole course, before it’s ever public. So, that builds it into the brickwork if you like. (10)

While the importance of advancing decolonising practices was uniformly supported, leaders also commented on some of the barriers to supporting biculturalism. A number of leaders noted the heavy load carried by Mãori staff, which included: teaching Mãtauranga Mãori, supporting Mãori students, managing external relationships with Mãori and partnering with non-Mãori staff. This requires targeted support by non-Mãori and by leaders of programmes:

This is the issue too for Mãori staff members having to wear all the curriculum that’s Mãori, and a pastoral care that’s Mãori, and do we support those Mãori staff members in the way that they should be and need to be, and ought to be cared for? (12)

Most leaders noted the challenge of finding and developing Mãori staff, and for some it was their biggest impediment to running a Tiriti-based programme.

Some leaders were in a position to grow their own Mãori workforce which might include scholarship and assistance programmes along with innovative funding support. Where an institution had its own master’s qualification, it tended to be easier to support Mãori staff to get that qualification, and then become employed as academics.

Given the importance of recruiting and retaining Mãori staff, it was particularly heart- breaking for programmes to have to let expert Mãori staff and other specialists go because they could not meet all the Social Workers Registration Board (SWRB) relatively recently introduced academic staff requirements:

The sad thing for us is that we lost them [expert Mãori staff ] in the last couple of years. And we lost them actually primarily around the SWRB requirements, which I think has been quite sad for us as a programme. (13)

Losing staff in this way created significant challenges for programmes as it also impacted on the sustainability of the movement toward bicultural practice. There was always the risk that one or more key staff would leave and affect the momentum of the whole programme.

Enablers of decolonising practice

Working on a shared values-base was considered to be an important first step in creating the environment within which decolonising practices could flourish. It was notable that linking team values to Mãtauranga Mãori has helped departments in their Tiriti-based journey by providing a solid foundation for development:

That shifted staff thinking, and what they did was exactly what I asked them to do, which was linking between (the) Treaty and where people were at with that; but also, Mãtauranga Mãori, and also the values we’ve adopted as a team. (11)

A number of leaders were optimistic about what was already going well in their programmes and saw the potential for them to become enablers of decolonising practices more broadly across their own institutions and the wider social service sector in Aotearoa NZ. Indeed, this was an imperative:

I think Aotearoa is looked at, and looked upon, as being quite progressive in this area. So, in our profession we need to be driving this and leading this; or else, people from other broader social service professions will drive and lead it for us. (13)

Leadership, and in particular Mãori leadership, was seen as a critical enabler of decolonising practice in social work education. Seeing this as part of a sector-wide development of Tiriti-based social work education was considered important to the overall sustaining of decolonising practices. Non-Mãori support was also considered important to the advancement of Mãori interests and leadership.

Having a close relationship with local iwi (tribes) and having iwi members involved in the programme was also seen as an enabler of decolonising practice. One of the sector-

wide initiatives involving Mãori leadership was the development of the draft Kaitiakitanga Framework. This would potentially create a more detailed set of standards around Tiriti- based practices in programmes, a significant gap for the SWRB regulator currently.

Further questions arose for a Kaupapa Mãori based programme in considering how it might partner with a mainstream programme on something like co-publishing but still have an honourable relationship with mutual benefit. Other leaders noted the value of doctoral research and publications such as Te Kõmako (a Mãori focused edition of the Aotearoa NZ social work journal) that targeted Tiriti based social work practice and education.

DISCUSSION

The findings have established the importance of Te Tiriti for social work educators and the fundamental place and value it brings to the profession. It is seen as critical in advancing decolonising practices in Aotearoa New Zealand. Indeed, the way in which Te Tiriti influences Aotearoa New Zealand law, policies and practice across the whole of government, its institutions and various public sector type groups reinforces a strong commitment to honouring Te Tiriti and partnering with Mãori more broadly. Notwithstanding the long struggle that Mãori have led and continue to lead so that Te Tiriti is honoured, Te Tiriti provides an over- arching influence upon Aotearoa New Zealand, arguably creating what Andrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock (2016) call an “authorizing environment” (Andrews et al., 2016, p. 2).

Originally derived from the work of Moore (2013), the notion of an authorising environment has been developed by Andrews et al. (2016) as a way of critically influencing organisational behavior, and providing legitimacy and accountability for action. This idea has recently also been developed to include human services work, for example see Connolly, Healey, and Humphreys (2017). Andrews et al. (2016) notes, however, that creating an authorising environment is not always easy, particularly when systems “are commonly fragmented, and difficult to navigate” (Andrews et al., 2016, p. 5). Given the nature of entrenched White privilege underpinning structures, policies and programmes, there is an institutional bias toward the dominant colonial discourse. Therefore, both establishing appropriate authority and also undertaking the agreed change can be difficult to secure, even more so when the problems being addressed are often wicked in nature due to their size and complexity. This further highlights the importance of a strong base of authority and inherent influence from which to operate.

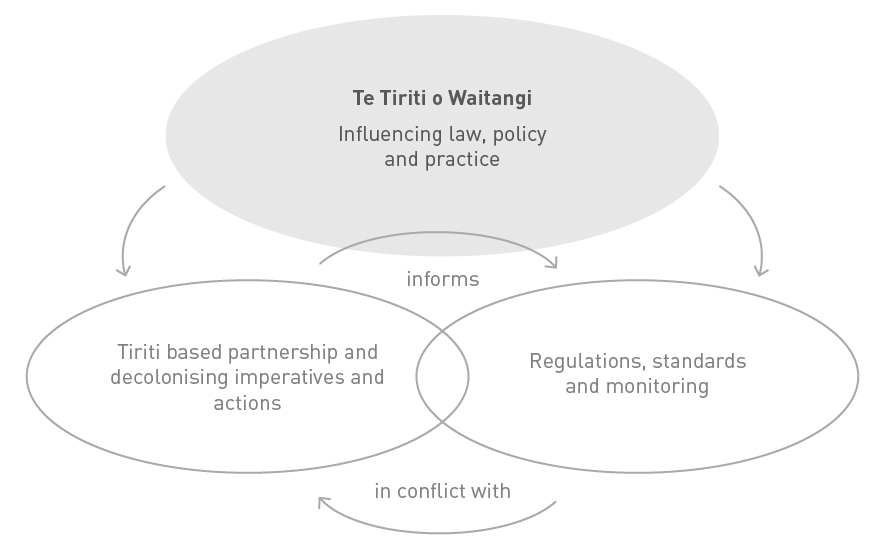

In the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, the concept of Te Tiriti as creating a foundational and ubiquitous authorising environment is particularly useful as it illustrates how influence can permeate aspects of government, social and economic policy, and law. The pursuit of Tiriti based partnership and decolonisation is a major initiative that involves both government and non-government agencies in Aotearoa New Zealand working together for its achievement albeit with varying levels of commitment. If we apply the notion of an authorising environ- ment to Te Tiriti and its implementation within tertiary social work education, then we can conceptualise the way in which it influences and legitimises Tiriti-based partnership and decolonising practices (Figure 1).

From the findings of this research it is clear that a strong, authorising environment creates the scaffolding necessary for the sharing of high-level goals and their implementation in service delivery. At the same time, the research also illustrates the tensions that can exist when government imperatives give effect to conflicting expectations. The area of regulation and standards which are contained in the remit of the regulatory body in Aotearoa New Zealand, the Social Workers Registration Board (SWRB), provides a good example of this (Figure 1). Recent requirements that social work educators have a master’s or doctoral degree (SWRB, 2017), has meant some Mãori staff have been lost to programmes. This directly weakens the Mãori workforce in contradicting the decolonising aims of Te Tiriti that specifically privileges Mãori interests. Indeed, it also critically weakens the SWRB’s own goal of producing graduates who are competent to practice social work with Mãori (SWRB, 2016).

Although the social work profession is well represented on the SWRB, the entity nevertheless intersects with government as the Social Workers Registration Act (2003) requires the Board to report directly to a government minister who is ultimately responsible for the standards it establishes and monitors. This regulatory responsibility creates a fundamental tension with the Crown’s imperative to advance and operationalise Te Tiriti. Ultimately, conflicting expectations have operational consequence for social work education programmes.

Although a heavy responsibility for creating safe practice systems rests with the SWRB, particularly in the context of child protection and risk-focused practice (Connolly, 2017), unless the regulatory body also pays attention to, and incorporates the decolonising expectations of Te Tiriti, social work education programmes will continue to be constrained in advancing Tiriti based imperatives.

It is clear that leadership activism by Mãori and non-Mãori allies is needed to work through these complexities, and to move forward in ways that are consistent with the clear requirements of Te Tiriti and the partnership expectations it presents. A ray of light within

the regulatory environment of social work education is seen in the Kaitiakitanga Framework which fleshes out the implications of honouring Te Tiriti and of further clarifying priorities in terms of “competence to practise social work with Mãori” (SWRB, 2016, para. 4). While early in its development, this strategic partnership between the SWRB and Mãori social work educators and practitioners has the potential to break through what has become something of an impasse that places real constraints on the development of Te Tiriti based social work education and practice.

CONCLUSION

Te Tiriti is a major feature of the Aotearoa New Zealand landscape that provides a strong, authorising environment for the advancement of decolonising practices in social work education. This has created a public discourse around Te Tiriti that has supported its growing influence. This authorising environment has, nevertheless, been critical for Tiriti based social work practice to develop in Aotearoa New Zealand where both government and non-government bodies are inextricably involved.

Like Aotearoa New Zealand, countries with colonial histories either have treaties with their Indigenous peoples, or are exploring these possibilities. For example, Australia is in the process of considering a treaty between the state of Victoria and Aboriginal peoples (The Guardian, 2018), something that this research suggests could ultimately scaffold the development of a partnership to integrate Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledges. In this context, the implementation of the recently developed Getting it Right framework (Zubrzycki et al., 2014), a major policy document for decolonising social work education in Australia, could be enabled by a stronger, authorising environment over time.

Notwithstanding the strength of the authorising environment, however, it is clear that regulatory frameworks can also present challenges to the attainment of decolonising practices. This research reinforces the importance of resolving regulatory misalignments with Te Tiriti imperatives in Aotearoa New Zealand. As efforts toward the mandatory registration of social workers in Australia intensify, ensuring regulatory alignment with decolonising ideals will also be important to the development of partnerships that integrate Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledges in social work education and practice.

References

Akhter, S. (2013, July). The bicultural lens of Te Wananga o Aotearoa: A journey of spiritual transformation. Paper presented at Critiquing Pasifika Education Conference @ the University, 4th biennial conference, AUT University Conference Centre. Auckland, NZ.

Akhter, S. (2015). Reimagining teaching as a social work educator: A critical reflection. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education. 17(1), pp.39-51.

Andrews, M., Pritchett, L., & Woolcock, M. (2016). Managing your authorizing environment in a PDIA process. CID Working Paper No. 312. Retrieved from https://bsc.cid.harvard.edu/publications/managing-your-authorizing-environment-pdia-process

Anglem, J. (2009). Some observations on social work education and indigeneity in New Zealand. In I. Thompson-Cooper &

G. Stacey-Moore (Eds.), Walking in the good way: Aboriginal social work education (pp. 133–140). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Aotearoa New Zealand Association of Social Workers. (2013). Code of ethics. Retrieved from http://anzasw.org.nz/ documents/0000/0000/0664/Chapter_3_Code_of_Ethics_Summary.pdf

Australian Association of Social Workers. (2012). Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) 2012 Guideline 1.4: Guidance on organisational arrangements and governance of social work programs. Retrieved from https:// www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/3552

Bennett, B. (2015). “Stop deploying your white privilege on me!” Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement with the Australian Association of Social Workers. Australian Social Work, 68(1), 19–31. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2013.840325

Bishop, A. (2003). Becoming an ally: Breaking the cycle of oppression in people (2nd Ed.). Sydney, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin. Brinkmann, S. (2013). Qualitative interviewing. Cary, USA: Oxford University Press.

Connolly, M. (2017). Beyond the risk paradigm in child protection. London, UK: Palgrave.

Connolly, M., Healey, L., & Humphreys, C. (2017). The collaborative practice framework for child protection and specialist domestic and family violence services – the PATRICIA Project: Key findings and future directions. Research to Policy and Practice, 3, June 2017. Sydney, Australia: ANROWS. Retrieved from https://www.anrows.org.au/publications/compass-0/patricia

Crawford, H. (Ed.). (2018). Effective social work education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Manukau Institute of Technology.

Eketone, A., & Walker, S. (2013). Kaupapa Maori social work research. In T. Hetherington, M. Gray, J. Coates, & M. Yellow Bird (Eds.), Decolonizing social work (pp. 259-270). Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

Faleolo, M. (2013). Authentication in social work education: The balancing act. In C. Noble, M. Henrickson, & I. Y. Han (Eds.), Social work education: Voices from the Asia Pacific (2nd ed., pp. 105–132). Sydney, NSW, Australia: Sydney University Press.

Fejo-King, C. (2013). Let’s talk kinship: Innovating Australian social work education, theory, research and practice through Aboriginal knowledge: Insights from social work research conducted with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory. Torrens, ACT, Australia: Christine Fejo-King Consulting.

Fejo-King, C., & Mataira, P. J. (Eds.) (2015). Expanding the conversation: International indigenous social workers insights into the use of indigenist knowledge and theory in practice. Torrens, ACT, Australia: Christine Fejo-King Consulting.

Gohori, J. (2017). From western-rooted professional social work to Buddhist social work. Tokyo, Japan: Gakubunsha.

Gray, M., Coates, J., Yellow Bird, M., & Hetherington, T. (Eds.). (2013). Decolonizing social work. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. Harms Smith, L., & Nathane, M. (2018). #NotDomestication #NotIndigenisation: Decoloniality in social work education.

Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 30(1), 1-18. doi: 10.25159/2415-5829/2400

Hendrick, A., & Young, S. (2018). Teaching about decoloniality: The experience of non-indigenous social work educators.

American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3–4), 306–318. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12285

Huygens, I. (2016). Pãkehã and Tauiwi treaty education: An unrecognised decolonisation movement? Kõtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2016.1148057

Johnson, S. (2010). Wicihitowin: Aboriginal Social Work in Canada. BC Studies, 167, 140.

Kreitzer, L. (2008). Decolonizing social work education in Africa: A historical perspective. In J. Coates, M. Yellow Bird, & M. Gray (Eds.), Indigenous social work around the world (pp. 185-206). Abingdon, UK: Ashgate.

Mafile’o, T. (2004). Exploring Tongan social work: Fekau’aki(connecting) and Fakatokilalo(humility). Qualitative Social Work, 3(3), 239–257. doi/10.1177/1473325004045664

Mafile’o, T., & Vakalahi, H. F. O. (2018). Indigenous social work across borders: Expanding social work in the South Pacific.

International Social Work, 61(4), 537–552.

McNabb, D. (2019). Pursuing equity in social work education: Democratising practices in Aotearoa New Zealand. Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

McNabb, D. J., & Connolly, M. (2019). The relevance of Global Standards to social work education in Australasia. International Social Work, 62(1), 35–47. doi:10.1177/0020872817710547

McNabb, D. (2017). Democratising and decolonising social work education: Opportunities for leadership [online]. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(1), 121–126.

Merja, L., Sanna, V., Merja, L., & Sanna, V. (2016). Social work practices and research with Sámi people and communities in the frame of indigenous social work. International Social Work, 59(5), 583–586.

Moore, M. H. (2013). Recognizing public value. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Morelli, P. T., Mataira, P. J., & Kaulukukui, C. M. (2013). Indigenizing the curriculum: The decolonization of social work education in Hawai’i. In T. Hetherington, M. Gray, J. Coates, & M. Y. Bird (Eds.), Decolonizing social work (pp. 207–222). Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

Muller, L. (2014). A theory for indigenous Australian health and human service work: Connecting indigenous knowledge and practice. Crows Nest, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Nikku, B. R., & Hatta, Z. A. (2014). Social Work Education and Practice: scholarship and Innovations in the Asia Pacific. Brisbane, QLD, Australia: Primrose Hall Publishing.

Noble, C., Henrickson, M., & Han, I. Y. (2013). Social work education: Voices from the Asia Pacific. Sydney, Australia: Sydney University Press.

Noble, C., Strauss, H., & Littlechild, B. (2014). Global social work: Crossing borders, blurring boundaries. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Sydney University Press.

Orange, C. (2015). The story of a treaty. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books.

Pease, B. (2016). Interrogating privilege and complicity in the oppression of others. In B. Pease, S. Goldingay, N. Hosken, & S. Nipperess (Eds.), Doing critical social work: Transformative practices for social justice (pp. 89–103). Crows Nest, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Ruwhiu, L., Te Hira, L., Eruera, M., & Elkington, J. (2016). Borderland engagements in Aotearoa New Zealand: Te Tiriti and social policy. In J. Maidment & L. Beddoe (Eds.), Social policy for social work and human services in Aotearoa New Zealand: Diverse perspectives (pp. 79–93). Christchurch, NZ: Canterbury University Press.

Singleton, G. E. (2015). Courageous conversations about race: A field guide for achieving equity in schools (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Social Workers Registration Board. (2016). Competence. Retrieved from http://swrb.govt.nz/competence-assessment/core- competence-standards

Social Workers Registration Board. (2017). Programme recognition standards. Retrieved from http://swrb.govt.nz/about-us/ policies/

Tamburro, A. (2013). Including decolonization in social work education and practice. Journal of Indigenous Social Development.2(1), 1-6.

The Guardian. (2018, June 21). Victoria passes historic law to create Indigenous treaty framework. Retrieved from https://www. theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/jun/22/victoria-passes-historic-law-to-create-indigenous-treaty-framework?CMP=Share_ iOSApp_Other

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). London, England: Zed Books.

Unitec Institute of Technology. (2011). Poutama. Retrieved from https://www.unitec.ac.nz/ahimura/publications/Poutama for Distribution and Publication.pdf

United Nations. (2008). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Waitangi Tribunal. (n.d.). Waitangi Tribunal - Reports. Retrieved from https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/publications-and- resources/waitangi-tribunal-reports/

Waterfall, B. F. (2008). Decolonizing Anishnabec social work education: An Anishnabe spiritually-infused reflexive study.

Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

Yellow Bird, M. (2016). Neurodecolonization: Applying mindfulness research to decolonizing social work. In M. Gray, J. Coates,

M. Yellow Bird, & T. Hetherington (Eds.), Decolonizing social work (pp. 293–310). Farnham, UK: Routledge.doi. org/10.4324/9781315576206

Young, S., & Zubrzycki, J. (2011). Educating Australian social workers in the post-apology era: The potential offered by a “whiteness” lens. Journal of Social Work, 11(2), 159–173. doi.org/10.1177/1468017310386849

Young, S., Zubrzycki, J., Green, S., Jones, V., Stratton, K., & Bessarab, D. (2013). “Getting it right: Creating partnerships for change”: Developing a framework for integrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in Australian social work education. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22(3–4), 179–197. doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2013.843120

Yuen-Tsang, A., & Ku, B. (2008). A journey of a thousand miles begins with one step: The development of culturally relevant social work education and fieldwork practice in China. In J. Coates, M. Yellow Bird, & M. Gray (Eds.), Indigenous social work around the world (pp. 177-190). Abingdon, UK: Ashgate.

Zubrzycki, J., Green, S., Jones, V., Stratton, K., Young, S., & Bessarab, D. (2014). Getting it right: Creating partnerships for change. Integrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in social work education and practice. Teaching and learning framework. Sydney, Australia: Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching.

- Hits: 4352